Kamikochi and the Daikiretto

by Laura Dickey

(Boston, Massachusetts)

Laura tackling the Daikiretto

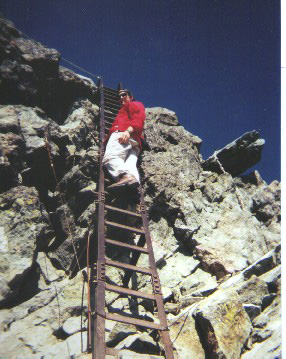

Jeff on ladder in the Daikiretto

On the 3rd day we began the portion of the hike called the "Daikiretto" (die-key-ret-toe - all I see is 'DIE'). Daikiretto means "the big cut." It is a knife edge ridge with chains (not that they keep you from falling) over long, very steep drops. To add to the excitement, the narrow (note the previous use of the term "knife edge") ridge and the steep drops happened to be covered with ice when we passed this section.

According to the Lonely Planet Guide to Hiking in Japan, the Daikiretto is the "most exhilarating and scariest bit of hiking in Japan that does not require any specialist skills." Apparently "specialist skills" do not include clawing up walls of ice, balancing on razor-thin (and ice-covered ledges), out-running landslides, cliff-leaping, nor flying.

I should have known something was up when we started the ascent on the first day. After hiking for about an hour, we noticed that many fellow hikers had a great deal of gear in tow; things like helmets, crampons, ice-picks, and small propellers. We thought they were overzealous.

There isn’t so much a trail on the Daikiretto – there are good ways to go (marked by ‘0’s), bad ways to go (marked by ‘X’s), and very, very bad ways to go (marked by a skull and crossbones, I’m not kidding – you get the point). The goal of hiking the Daikiretto is very simple: do not die.

The transition from average-joe-hiker terrain to but-you’ve-got-so-much-to-live-for terrain was gradual, so I almost didn’t realize that I was doing the splits in order to maneuver up technical stretches until I heard something that disturbed me: a helicopter.

Laura: Jeff, do you see a National Geographic logo on that helicopter?

Jeff: I’m sure it’s just coming to deliver supplies to the small metropolis that’s been developed atop this 11,500-foot mountain (that’s another story; see “Japanese Idea of Roughing it” section).

Laura: You don’t suppose that helicopter is coming to pick up somebody who has fallen to his untimely and grisly death?

Jeff: Of course not, Sweetie, nobody dies in Japan.

A few minutes later, we passed a Japanese man who, in his best English, said, “Herro. Prease take care when you go to up. It is bery srippery. Ice. Dangerous. You see hericopter? That hericopter came to get fallen man.” With that he bowed and departed.

We continued to slowly ascend what Jeff and I figured was about a 5.6-5.7 climb until we came to an impasse. We were standing on a ledge and had to cross over a 1.5-foot chasm (about 4500-ft deep) to a sheer, vertical cliff that had only three 6-inch iron bars (3/4 inch diameter) protruding for assistance. I stared at it for about 5 minutes, and then did the only logical thing I could think of: I started bawling. Jeff patiently patted my head and comforted me with words like, “If you die, it’s okay, because at least you’ve been baptized.” Finally he took my 20 lb pack and carried it over his 60 lb pack so that I could cross the abyss unfettered.

At the top of the cliff, we stopped to rest. Jeff suddenly cupped his ears and grew quiet.

Jeff: Laura, do you hear that noise?

Laura: What noise?

Jeff: The one that sounds like a giant rockslide?

Laura: Oh, that noise. What do you think it is?

Jeff: Uhh… a giant rockslide.

Laura: We’re on a mile-high pile of rocks. Do you think there could be a rockslide on this peak, too?

Jeff: Of course not, Sweetie, these are special rocks - they are unaffected by gravity, weather, erosion, and plate tectonics.

More helicopters. We continued - the day was growing late, and with every degree in temperature drop, I became a little more terrified. The terrain was getting steeper, the rocks were getting icier, and the helicopters were getting present-ier; their increasing buzz was a continual reminder that I was not safe. Not even a little safe. My head was spinning, so I sat down for another cry. Jeff pointed out that there were several old ladies who were passing me, and that I could surely out-hike them. He also mentioned that they weren’t crawling on the ground, feeling out every possible move before moving an inch. I think he was tempted to join them.

I did feel better at the top of one steep climb when we met some other Americans. I cheerfully asked, “How was it?” to which one of the tougher looking guys almost burst into tears and in a squeaky voice said, “This sucks.” The rest of them agreed; in fact, they were furious because they had read something about not needing any “specialist skills.” One guy said, “I go backpacking and climbing ALL THE TIME! I’m in great shape - people should not be doing this without ropes. I feel like I’m in some kind of horror movie…” I told him everything would be fine and to not be discouraged.

After several additional crying spells and a rather remarkable amount of patience on Jeff’s part, we reached the day’s destination: the Daikiretto Lodge, which happened to be situated between two large rockslide/avalanches waiting to happen. At this point, I should give you some background.

Jeff’s roommate Scott kindly let him borrow his sleeping bag; however, I was without one, so I took Jeff's comforter thinking that I would probably be roasting. Recall that Jeff mentioned we were hiking at 11,000-foot elevations, and add to that the fact that it was mid-OCTOBER. Trying to sleep was nothing less than a pure and undiluted agony.

Luckily, I had brought a year’s supply of hand-warmers - I’m pretty sure they’re the only reason I lived (oops, sorry for giving away the ending). Anyway, we also didn’t bring a camp-stove, so we were living off cold soup, beans, and curry wrapped in cold tortilla shells. Even the fact that we were exhausted, cold, and miserable didn’t make them taste good.

So we got to the Daikiretto Lodge, and decided it might be worth the 50,000 yen to have a warm bed, bathroom, and (God bless the Japanese for desecrating the environment in the name of capitalism) a WARM delicious meal. We had to sleep in a room with about 60 others, 58 or so of which were old Japanese men with sleep apnea problems, but we managed to sleep through the snoring for at least 5 or 6 hours and (God bless Japan) we were warm.

The next morning, we wanted to get an early start, but after hiking for about three minutes on relatively flat ground that even had a trail, I started to slump down to the previous day’s crawl and declared myself unfit to continue because my hands were cold. Jeff took me back to the lodge, bought me some gloves, and sat me down by the heater. He said, “I think maybe this has been too much for you. Let’s take the shortcut down.”

With quivering lips, and in a very childlike whine, I said, “But I don’t WANT to take the shortcut!” He said, “I know, but I don’t want this to damage your psyche permanently, and I’d kind of like to get off this mountain before the New Year.” I took a deep breath, and told him I was ready to climb the last peak – that I would be lionhearted and try so hard to stay vertical.

I made it up the last peak, but you wouldn’t believe it – the last peak went back down, which meant more chains, ladders, and bloody hands. At one point, as I was hiking with a Czechoslovakian woman named Sandra, we saw a man who seemed to be guarding the path down the mountain. He pointed to a sheer cliff (with chains) and, beaming, informed us that "This year, five people die here. This year!" Sandra and I thanked him for warning us, while Jeff and Sandra’s boyfriend tried to push him off the cliff for putting undue fear into our hearts.

As we were carefully making our way down, we saw a group of old people standing around in confusion as they tried to determine the best course. One man tried to go down a particular portion, and fell. We all watched silently as he rolled, and rolled, and rolled, and stopped.

Finally, somebody not in our group yelled, “Daijobu desu ka?” (Are you OK?). The man lifted his head and yelled, “Daijobu!” and we all started breathing again. It’s not to our credit that we were too shocked to think that the old man might want some help up; instead, we noted to each other that he had gone down some rocks with a skull and crossbones painted on them, and that he shouldn’t have done that.

Well, we moved on and when we got to the bottom of the mountain, I kissed the ground several times and begged Jeff to promise me that we’d do it again.